Stress is an omnipresent aspect of modern life, an invisible undercurrent that can ripple through your daily experiences, affecting your cognitive performance, emotional well-being, and even your physical health. While often perceived as purely psychological, stress is, at its core, a neurobiological phenomenon. Understanding the intricate dance between your brain and your body during periods of stress, and conversely, during states of focused calm, provides you with a powerful toolkit for navigating life’s challenges. This article will delve into the neuroscience of stress relief and focus, offering you insights into the mechanisms at play and practical strategies for optimizing your cognitive resilience.

Imagine your brain as a highly sophisticated supercomputer, constantly processing streams of data from your internal and external environments. When faced with a perceived threat, this supercomputer initiates a rapid, cascading series of events known as the stress response. This is not a flaw in your design; it is an ancient, hardwired survival mechanism evolutionarily honed to protect you from danger.

The Amygdala’s Role: The Fear Hub

At the heart of this initial alarm is your amygdala, a small, almond-shaped structure deep within your temporal lobe. The amygdala acts as your brain’s fear detector, a vigilant sentinel constantly scanning your surroundings for potential threats. When it perceives danger, whether it’s a growling predator in the savanna or a looming deadline at work, it immediately sounds the alarm. This alarm is not a nuanced, logical assessment; it’s a quick, impulsive reaction designed for speed over accuracy. Your amygdala doesn’t distinguish between a lion and a loud car horn in terms of its initial warning signal.

The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) Axis: The Stress Hormone Command Center

Upon activation, the amygdala sends urgent signals to your hypothalamus, a region in your brain responsible for maintaining homeostasis. The hypothalamus, in turn, initiates the activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, often referred to as your body’s central stress response system.

- Corticotropin-Releasing Hormone (CRH): Your hypothalamus releases CRH, a peptide hormone that acts as the initial messenger in this complex chain.

- Adrenocorticotropic Hormone (ACTH): CRH then travels to your pituitary gland, which responds by secreting ACTH into your bloodstream.

- Cortisol Release: ACTH races down to your adrenal glands, situated atop your kidneys, triggering them to release cortisol. Cortisol is your primary stress hormone, often dubbed the “stress steroid.”

Cortisol has a wide-ranging impact on your body, preparing you for either “fight or flight.” It increases blood sugar for immediate energy, suppresses non-essential bodily functions like digestion and immune response, and raises your heart rate and blood pressure. While crucial for acute survival, chronic elevation of cortisol can have detrimental effects on your brain and body, leading to inflammation, impaired memory, and a dampened immune system.

The Sympathetic Nervous System: The Accelerator Pedal

Concurrently with the HPA axis activation, your brain also revs up your sympathetic nervous system (SNS), a branch of your autonomic nervous system. Think of your SNS as the accelerator pedal of your car.

- Adrenaline (Epinephrine) and Noradrenaline (Norepinephrine): Your SNS directly stimulates your adrenal medulla to release adrenaline and noradrenaline. These neurotransmitters are responsible for the immediate physical manifestations of stress: pounding heart, rapid breathing, dilated pupils, and increased blood flow to your muscles. This surge of energy is designed to empower you to confront or flee a perceived threat.

This intricate neurobiological cascade is what you experience as the feeling of stress. It’s a powerful, evolutionarily conserved mechanism, but in our modern world, it’s often triggered by psychological stressors rather than immediate physical dangers, leading to a state of chronic activation that can have significant consequences.

In exploring the neuroscience of stress relief and focus, a fascinating article can be found at Productive Patty, which delves into the mechanisms by which mindfulness and meditation can enhance cognitive function and reduce stress levels. This resource provides valuable insights into how these practices can reshape our brain’s response to stress, ultimately fostering a more focused and productive mindset.

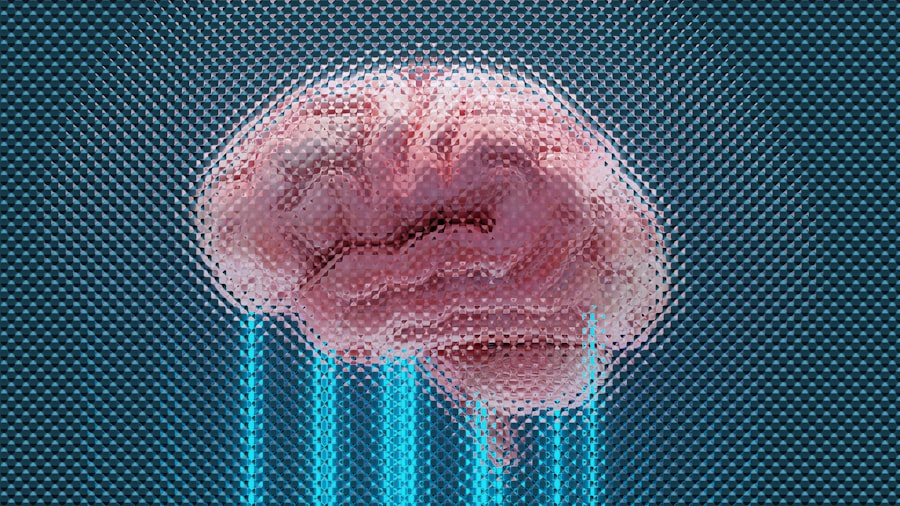

The Prefrontal Cortex: Your Brain’s Executive Conductor

While your amygdala is the alarm system and your HPA axis and SNS are the fuel injectors, your prefrontal cortex (PFC) is the conductor of your brain’s intricate orchestra. Located at the very front of your brain, the PFC is responsible for executive functions, including planning, decision-making, working memory, attention, and regulating emotions. It is your inner CEO, the part of your brain that allows you to think rationally, make reasoned judgments, and modulate your emotional responses.

Prefrontal Cortex and Stress: A Tug-of-War

When stress levels are low to moderate, your PFC generally functions optimally, allowing you to remain focused and make sound decisions. However, under high-stress conditions, your PFC’s capacity can be significantly compromised. The surge of stress hormones, particularly cortisol, can impair the functioning of your PFC. It’s as if the conductor is overwhelmed by the cacophony of the alarm, struggling to maintain control of the orchestra.

- Impaired Working Memory: You might find it difficult to hold information in your mind, leading to forgetfulness and errors.

- Reduced Decision-Making Capacity: Your ability to weigh options and make logical choices can diminish, leading to impulsive or biased decisions.

- Difficulty with Emotional Regulation: You might experience heightened irritability, anxiety, or emotional outbursts, as your PFC struggles to put the brakes on your amygdala’s alarm bells.

This interplay illustrates a critical concept: the more activated your amygdala and stress response systems are, the less effective your PFC becomes. This creates a vicious cycle, where heightened stress impairs your ability to cope, further escalating your stress levels.

The Prefrontal Cortex in Focus: Sharpening Your Mental Edge

Conversely, a well-functioning PFC is paramount for states of focus and concentration. When you are engaged in a task that requires sustained attention, your PFC is actively involved in filtering out distractions, maintaining your goal, and inhibiting irrelevant thoughts and actions.

- Selective Attention: Your PFC allows you to selectively attend to relevant stimuli while ignoring distractions, like a spotlight illuminating the most important elements of a scene.

- Goal-Directed Behavior: It keeps your actions aligned with your objectives, preventing you from drifting off task.

- Cognitive Flexibility: It enables you to switch between tasks and adapt your approach as needed.

Training your PFC to become more robust and resilient is a key strategy for both stress relief and enhanced focus.

Neuroplasticity: Sculpting Your Brain for Resilience

One of the most remarkable aspects of your brain is its neuroplasticity – its ability to change and adapt throughout your life in response to experiences, learning, and environmental demands. This capacity means that your brain is not static; it’s a dynamic, ever-evolving landscape.

Stress and Brain Remodeling: The Dark Side of Plasticity

While neuroplasticity generally evokes positive connotations, it also means that chronic stress can literally reshape your brain in undesirable ways. Prolonged exposure to cortisol can lead to:

- Shrinkage of the Hippocampus: The hippocampus, a brain region critical for learning and memory and for regulating the HPA axis, can shrink under chronic stress. This contributes to impaired memory and an inability to “turn off” the stress response.

- Enlargement of the Amygdala: Conversely, chronic stress can lead to an enlargement of the amygdala, making you more prone to anxiety and fear responses. It’s like constantly exercising your fear muscle, making it stronger and more reactive.

- Reduced Connectivity in the PFC: The connections within your prefrontal cortex can also be weakened, further impairing executive functions.

These structural and functional changes underscore the importance of stress management not just for your immediate well-being but for the long-term health and efficiency of your brain.

Cultivating Positive Plasticity: The Path to Resilience

The good news is that you can harness neuroplasticity to your advantage, actively sculpting your brain for greater resilience and focus. Engaging in specific practices can strengthen beneficial neural pathways and even promote the growth of new brain cells (neurogenesis) in areas like the hippocampus.

- Mindfulness and Meditation: Regular mindfulness practice has been shown to increase gray matter density in the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus, while simultaneously reducing amygdala activity. It’s like strengthening your PFC’s ability to act as a wise observer, rather than being swept away by emotional storms.

- Exercise: Physical activity is a powerful neurobiological intervention. It releases neurotrophic factors, such as Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF), which act like fertilizer for your brain, promoting the growth and survival of neurons and enhancing synaptic plasticity.

- Learning and Novel Experiences: Continuously challenging your brain with new learning experiences keeps it agile and promotes the formation of new neural connections, particularly in the PFC.

By actively engaging in these practices, you are essentially providing your brain with the raw materials and training it needs to become more robust, adaptable, and less susceptible to the ravages of chronic stress.

Neurotransmitters: The Chemical Messengers of Mood and Focus

Your brain communicates through a complex symphony of chemical messengers called neurotransmitters. These tiny molecules transmit signals between neurons, influencing everything from your mood and emotions to your ability to focus and learn.

The Role of Key Neurotransmitters in Stress and Focus

Understanding the interplay of these neurotransmitters provides further insight into how stress impacts your cognitive abilities and how you can optimize your brain chemistry for better performance and well-being.

- Dopamine: The Reward and Motivation Molecule: Dopamine is crucial for feelings of pleasure, motivation, and reward. It plays a significant role in attention and focus. Under stress, dopamine levels can become dysregulated, affecting your ability to stay motivated and engaged. Practices that evoke a sense of achievement and progress can help to optimize dopamine pathways.

- Serotonin: The Mood Regulator: Serotonin is widely associated with feelings of well-being, happiness, and calmness. Low serotonin levels are often linked to depression and anxiety. Chronic stress can deplete serotonin, contributing to feelings of unease. Activities that promote positive social interaction, exposure to sunlight, and a healthy diet can support healthy serotonin levels.

- Norepinephrine: The Alertness Amplifier: While also a stress hormone, norepinephrine, as a neurotransmitter, is essential for alertness, vigilance, and focus. However, excessive levels due to chronic stress can lead to anxiety and agitation. Finding the right balance is key. Moderate physical activity can help regulate norepinephrine.

- GABA: The Brain’s Natural Calming Agent: Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) is the primary inhibitory neurotransmitter in your brain. It acts like a brake, slowing down neural activity and promoting a sense of calm and relaxation. When GABA is deficient, you might experience increased anxiety and restlessness. Mindfulness, deep breathing exercises, and certain dietary choices can enhance GABAergic activity.

- Acetylcholine: The Learning and Memory Enhancer: Acetylcholine is vital for learning, memory, and sustained attention. It plays a critical role in the functioning of your prefrontal cortex. Practices that involve focused attention and novelty can support acetylcholine production and release.

By understanding how these neurotransmitters contribute to your mental states, you can adopt habits and engage in activities that naturally promote a more balanced and optimal neurochemical environment within your brain.

Recent studies in the neuroscience of stress relief and focus have highlighted the importance of mindfulness practices in enhancing cognitive function and emotional well-being. For those interested in exploring this topic further, a related article can be found at Productive Patty, which delves into various techniques that can help individuals manage stress and improve their concentration. By incorporating these strategies into daily routines, people can cultivate a more focused and resilient mindset.

Practical Neurobiological Strategies for Stress Relief and Focus

| Metric | Description | Typical Range/Value | Relevance to Stress Relief and Focus |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cortisol Levels | Hormone released in response to stress | Normal: 6-23 mcg/dL (morning) | High cortisol impairs focus; reduction linked to stress relief |

| Heart Rate Variability (HRV) | Variation in time between heartbeats | Higher HRV indicates better autonomic regulation | Increased HRV correlates with improved stress resilience and focus |

| Prefrontal Cortex Activity | Brain region involved in attention and executive function | Measured via fMRI or EEG; increased activity during focus | Enhanced activity supports sustained attention and stress regulation |

| Alpha Brainwave Power | EEG frequency band (8-12 Hz) associated with relaxation | Increased alpha power during relaxed, focused states | Higher alpha power linked to reduced stress and improved focus |

| Gamma Brainwave Power | EEG frequency band (30-100 Hz) linked to cognitive processing | Elevated gamma during intense focus and memory tasks | Increased gamma activity correlates with enhanced attention and cognitive control |

| Salivary Alpha-Amylase | Enzyme marker of sympathetic nervous system activity | Elevated levels indicate acute stress response | Lower levels post-intervention suggest effective stress relief |

| BDNF (Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor) | Protein supporting neuron growth and plasticity | Increased levels after mindfulness and exercise | Higher BDNF enhances cognitive function and stress resilience |

Armed with an understanding of the underlying neuroscience, you can now implement targeted strategies to mitigate stress and enhance your ability to focus. These are not merely “feel-good” practices; they are neurobiologically informed interventions that actively reshape your brain.

Mindfulness and Meditation: Rewiring Your Brain for Calm

Engaging in mindfulness and meditation is arguably one of the most powerful neurobiological tools you possess. When you practice mindfulness, you are intentionally directing your attention to the present moment, observing your thoughts, feelings, and bodily sensations without judgment.

- Reduced Amygdala Activity: Studies using fMRI show that regular meditation can lead to decreased activity in the amygdala, effectively reducing your brain’s fear response.

- Increased PFC Connectivity: Meditation strengthens the connections between your prefrontal cortex and your amygdala, allowing your “wise CEO” to have greater influence over your emotional reactions. This gives you more regulatory control over your stress response.

- Enhanced Hippocampal Volume: Long-term meditators often exhibit increased gray matter volume in the hippocampus, improving memory, learning, and the ability to regulate cortisol.

- Alpha and Theta Brainwave Enhancement: Meditation promotes the generation of alpha and theta brainwaves, which are associated with states of relaxation, creativity, and deep focus.

Start with short, consistent sessions, even just 5-10 minutes daily. Focus on your breath, observe your thoughts without getting entangled in them, and gently redirect your attention back to the present moment when your mind wanders. This practice is akin to training a muscle; the more you do it, the stronger your capacity for calm and focus becomes.

Physical Exercise: A Full-Body Brain Booster

You might view exercise primarily as a way to maintain physical fitness, but its impact on your brain is profound, offering a potent antidote to stress and a catalyst for focus.

- Stress Hormone Reduction: Regular physical activity helps to metabolize and clear out excess stress hormones like cortisol and adrenaline, effectively hitting the reset button on your stress response system.

- Neurotransmitter Symphony: Exercise boosts the production of beneficial neurotransmitters such as dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine, improving mood, motivation, and alertness. It also releases endorphins, your body’s natural painkillers and mood elevators.

- BDNF Production and Neurogenesis: As mentioned earlier, exercise significantly increases Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF), promoting the growth of new neurons and strengthening existing neural connections, particularly in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex. This is directly linked to improved learning, memory, and cognitive function.

- Improved Sleep Quality: Exercise, especially when performed earlier in the day, helps regulate your circadian rhythm and promotes deeper, more restorative sleep, which is crucial for brain health and stress recovery.

Aim for a combination of cardiovascular exercise and strength training. Even short bursts of movement throughout the day can be beneficial. Your brain will thank you.

Strategic Breaks and Deep Work: Fueling Your Focus Engine

Your brain, like any complex machine, needs periods of intentional rest and focused activity to operate optimally. Constantly pushing yourself without breaks can lead to cognitive fatigue and decreased efficiency.

- Ultradian Rhythms: Your brain operates on natural cycles called ultradian rhythms, typically lasting around 90-120 minutes, during which you can maintain high levels of focus. After this, your brain naturally needs a short break to consolidate information and recharge. Ignore these signals, and your productivity will plummet, and stress will likely rise.

- The Pomodoro Technique: This popular time management method leverages these rhythms by structuring work into 25-minute focused intervals (“Pomodoros”) followed by short 5-minute breaks. After four Pomodoros, you take a longer break (15-30 minutes). This structured approach helps train your brain to sustain focus and prevents burnout.

- Nature Exposure: Stepping away from your screen and immersing yourself in nature, even for a few minutes, has measurable benefits. Studies show that spending time in green spaces can lower cortisol levels, reduce blood pressure, and improve mood. This isn’t just “feeling good”; it involves physiological changes in your stress response.

- Digital Detox: The constant barrage of notifications and information from digital devices can keep your amygdala subtly activated and prevent your PFC from fully engaging in sustained focus. Periodically disconnecting allows your brain to reset and re-focus its resources.

By intentionally structuring your work and rest periods, you are honoring your brain’s natural operating rhythms, thereby reducing stress and optimizing your capacity for deep, meaningful work.

In conclusion, understanding the neuroscience of stress relief and focus empowers you to move beyond simply “coping” with stress to actively shaping your brain for resilience and optimal performance. By engaging in practices that regulate your stress response, strengthen your prefrontal cortex, harness positive neuroplasticity, and balance your neurotransmitter systems, you gain greater control over your mental landscape. This journey is not about eliminating stress entirely, but about developing the neurobiological capacity to navigate it effectively, transforming challenges into opportunities for growth and deeper, more focused engagement with life.

FAQs

What is the neuroscience behind stress relief?

The neuroscience of stress relief involves understanding how the brain processes stress and activates mechanisms to reduce it. Key brain areas include the amygdala, which detects stress, and the prefrontal cortex, which helps regulate emotional responses. Neurotransmitters like serotonin and GABA play roles in calming the nervous system, while practices such as mindfulness and deep breathing can alter brain activity to promote relaxation.

How does stress affect brain function and focus?

Stress triggers the release of cortisol and adrenaline, which can impair the functioning of the prefrontal cortex, the brain region responsible for attention, decision-making, and focus. Chronic stress can lead to reduced cognitive performance, memory problems, and difficulty concentrating, as it disrupts neural circuits involved in executive function.

What brain mechanisms improve focus during stress relief techniques?

Stress relief techniques like meditation and controlled breathing enhance activity in the prefrontal cortex and increase connectivity with other brain regions, improving attention control. These practices also reduce amygdala hyperactivity, lowering emotional reactivity and allowing better cognitive focus.

Can neuroplasticity help in managing stress and improving focus?

Yes, neuroplasticity—the brain’s ability to reorganize itself—allows individuals to develop healthier stress responses and improve focus through repeated practice of stress management techniques. Over time, these changes can strengthen neural pathways associated with emotional regulation and attention.

What role do neurotransmitters play in stress relief and focus?

Neurotransmitters such as serotonin, dopamine, and GABA are crucial in regulating mood, anxiety, and attention. Increased levels of serotonin and GABA promote relaxation and reduce stress, while dopamine supports motivation and focus. Balancing these chemicals through lifestyle, diet, and stress relief practices can enhance overall brain function.