You’ve likely encountered it: that gnawing feeling, the subtle whisper that becomes a persistent hum, telling you that pushing forward might no longer be the wisest course. It’s the moment when the anticipated reward for your continued effort dims, and the scales of investment begin to tip precariously. This is the crucible of the art of quitting, a skill as vital, and often more challenging, than the perseverance you’ve been taught to champion. You are not expected to be a Sisyphus, eternally rolling a boulder uphill if the summit has vanished.

Unpacking the Concept: Beyond the Stigma of Failure

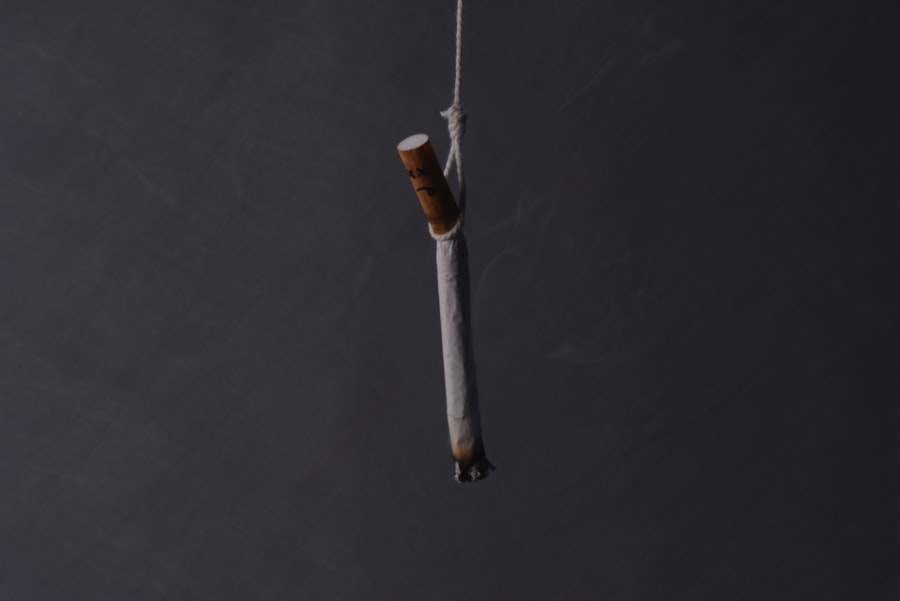

The prevailing narrative often lionizes the relentless striver, the individual who “never gives up.” While admirable in many contexts, this dogma can become a gilded cage, trapping you in situations that drain your resources without commensurate return. Quitting, in this light, is not an admission of defeat but a strategic recalibration, a conscious decision to reallocate your energy towards endeavors that offer a more fertile ground for growth and fulfillment. It’s about recognizing that sometimes, the most courageous act is to acknowledge when a path has become a dead end, a dried-up riverbed in a vast desert.

The Societal Conditioning of Persistence

From childhood, you are often bombarded with stories of triumph born from unwavering determination. Characters overcome insurmountable odds, their persistence the key to unlocking success. This narrative, while inspiring, can inadvertently foster a fear of acknowledging limitations. You learn to associate “quitting” with weakness, with a lack of character, with an inability to meet challenges head-on. This conditioning can be as potent as any personal resistance, making it difficult to even entertain the idea of disengaging. You are taught to see a closed door as an invitation to break it down, rather than an opportunity to find another entrance or, perhaps, to realize the building itself was not your intended destination.

Redefining “Failure” in the Context of Growth

The common understanding of “failure” often implies a permanent state of inadequacy. However, in a more nuanced view, failure is merely an outcome, a data point. When you experiment in a laboratory, not every hypothesis yields the expected results, yet this doesn’t render the experiment a failure. It provides valuable information that guides future investigations. Similarly, when you step away from a task or pursuit, it is not necessarily a failure of your capabilities but potentially a misallocation of those capabilities. The effort invested, even if it doesn’t lead to the desired endpoint, contributes to your accumulated knowledge and experience. You gain clarity on what doesn’t work, what doesn’t resonate, and what is no longer aligned with your evolving goals.

The Economic Principle of Opportunity Cost

At its core, the decision to quit often boils down to the economic principle of opportunity cost. Every hour you spend on a project that is yielding diminishing returns is an hour you are not spending on something else that could be far more beneficial. This “hidden cost” is one of the most persuasive arguments for strategic disengagement. Your time, energy, and mental resources are finite. Continuing to pour them into a situation where the expected outcome is meager is akin to watering a plant in barren soil. The water is used, but the plant will not flourish.

Identifying the Tipping Point: Recognizing Diminishing Returns

The art of quitting is not an impulsive act but a calculated one, grounded in the ability to identify when the effort required begins to outweigh the potential benefits. This involves a sober assessment of your current trajectory and a realistic projection of future outcomes. It requires you to step back from the emotional investment you’ve made and view the situation with a critical, objective lens.

The Ebbing Tide of Enthusiasm and Motivation

Initial enthusiasm can be a powerful engine, driving you forward with vigor. However, as obstacles arise and progress stalls, this engine can sputter. A sustained lack of motivation, a feeling of dread associated with the task, or a pervasive sense of obligation rather than inspiration are strong indicators that your passion may have been exhausted. It’s like staring at a long, winding road; at the beginning, the journey seems exciting, but after miles of monotony and unseen turns, the allure fades. You must ask yourself: Is this a temporary lull, or has the well of your inner drive run dry?

The Shifting Landscape of Goals and Priorities

Your personal and professional goals are not static; they evolve as you gain new experiences and perspectives. What once seemed critically important might, with time and reflection, become less so. The crucial insight here is to assess whether the task at hand is still aligned with your current aspirations. If you’ve embarked on a journey to a vibrant metropolis, but the road has led you to a desolate outpost, you must ask if this outpost still serves your original desire for urban exploration. Your priorities have likely shifted, and staying on a path that no longer serves your vision is a form of involuntary stagnation.

The Erosion of Tangible Progress and Measurable Outcomes

Quantifiable progress is a vital metric for assessing the viability of any endeavor. If you find yourself spinning your wheels, with minimal tangible achievements despite considerable effort, it’s a red flag. This might manifest as project milestones consistently being missed, creative output becoming stagnant, or the expected benefits failing to materialize despite repeated attempts. It’s like trying to build a house with crumbling bricks; no matter how much effort you exert, the structure will not withstand the test of time. You need to see the edifice of your efforts rising, not dissolving.

The Growing Shadow of Negative Consequences

Beyond the lack of positive returns, consider the potential negative consequences of continued engagement. This could include detrimental effects on your mental or physical health, the strain on your relationships, or the depletion of financial resources with no clear prospect of return. Are you sacrificing your well-being on the altar of a potentially fruitless pursuit? The perceived reward must be significant enough to justify the mounting toll. Continuing to invest in a sinking ship, even with the hope of rescuing the cargo, becomes irrational when the ship is inevitably taking you down with it.

The Mechanics of Disengagement: Crafting a Strategic Exit

Quitting does not have to be a messy, abrupt departure. A well-executed exit is often as important as the commitment to the original task. It requires foresight, planning, and a commitment to minimizing collateral damage. You are not simply abandoning a post; you are orchestrating a controlled withdrawal to better territories.

Communicating Your Decision with Clarity and Professionalism

When you decide to disengage from a work project, a collaborative effort, or even a personal commitment, clear and professional communication is paramount. This involves articulating your reasons without excessive justification or defensiveness. It’s about stating your decision forthrightly, acknowledging any impact, and offering to facilitate a smooth transition. Imagine you are a captain leaving a vessel; you don’t simply jump overboard. You make arrangements for the crew and the ship’s future.

Documenting and Handing Over Responsibilities

A responsible quitter ensures that their departure does not leave a vacuum or create undue burden on others. This might involve documenting your work, organizing your files, and providing thorough handovers to colleagues or successors. This act of professionalism demonstrates integrity and respect for the contributions of those who will continue the work. It’s the act of carefully packing your belongings and leaving your former dwelling in good order, making it easy for the next occupant to settle in.

Preserving Relationships and Maintaining Goodwill

Even when exiting a situation that proved unproductive, it’s generally advisable to maintain positive relationships. Burning bridges can have unforeseen negative consequences down the line. By acting with grace and maturity, you preserve the possibility of future collaborations or connections. You are not just closing a chapter, but ensuring the book of your network remains open for future stories.

Seeking Feedback and Learning from the Experience

A truly astute quitter doesn’t just walk away; they learn. Seeking feedback on why things didn’t work out, or reflecting on the lessons learned, is an invaluable part of the process. This introspection transforms a perceived setback into a stepping stone for future decision-making. It’s like a sailor reviewing their charts to understand why they were blown off course, so they can navigate more effectively next time.

The Psychology of Letting Go: Overcoming Internal Barriers

The decision to quit is often the easier part; the true challenge lies in the psychological process of letting go. You must confront internalized beliefs and emotional attachments that can make disengagement feel like a betrayal of yourself or others.

Confronting the Fear of Regret

The prospect of future regret is a powerful deterrent to quitting. You might worry that by walking away, you are forfeiting a potential reward that might have materialized had you persisted. This fear often stems from an inability to accurately predict the future. It is essential to trust your current assessment and acknowledge that hindsight is a luxury you cannot afford in the present. It’s like standing at a crossroads, paralyzed by the thought of taking the wrong path, yet never moving forward.

Releasing the Sunk Cost Fallacy

The sunk cost fallacy is the tendency to continue investing in something simply because you’ve already invested heavily in it, regardless of whether it’s still a rational decision. You’ve poured time, money, or effort into a situation, and the idea of letting that investment go feels wasteful. However, sunk costs are by definition unrecoverable. Continuing to invest based on past expenditure is like throwing good money after bad. You must accept that the past investment is gone and make decisions based on future potential. You cannot un-boil an egg, and you cannot reclaim the time already spent on a non-viable path.

Managing Feelings of Guilt and Obligation

You may feel guilty about letting down colleagues, superiors, or even yourself. This sense of obligation can be a powerful force, making it difficult to prioritize your own well-being or future prospects. However, true responsibility often lies in making the best decision for your long-term growth and effectiveness, even if it causes temporary discomfort to others. It’s like a doctor making a difficult diagnosis; the truth, though painful, is ultimately in the patient’s best interest.

Embracing the Liberating Power of a Fresh Start

Once the decision is made and the exit is managed, a profound sense of liberation can follow. Letting go of a burdensome task or unproductive situation frees up mental and emotional bandwidth. This space can be filled with new opportunities, renewed energy, and a clearer vision for what you truly want to pursue. It’s like a hiker finally reaching the summit and then descending into a valley of new trails, each holding the promise of fresh exploration.

The Long-Term Benefits of Knowing When to Walk Away

The ability to strategically quit is not merely a survival tactic; it is a hallmark of a mature and effective individual. It cultivates resilience, enhances decision-making, and ultimately leads to a more fulfilling and productive life.

Increased Focus and Productivity on Aligned Ventures

By disengaging from draining pursuits, you free yourself to concentrate on those that truly matter. This enhanced focus allows for greater depth of engagement and, consequently, higher levels of productivity and achievement in areas that align with your core values and goals. You are no longer a jack-of-all-trades, but a master of a chosen few.

Enhanced Self-Awareness and Emotional Intelligence

The process of identifying the tipping point, making the decision, and executing the exit significantly sharpens your self-awareness. You gain a deeper understanding of your motivations, your limits, and your priorities. This introspection fosters greater emotional intelligence, enabling you to navigate future challenges with greater wisdom and composure. You become a more astute observer of your own internal landscape.

A More Fulfilling and Purposeful Life Path

Ultimately, the art of quitting, when practiced wisely, allows you to curate a life path that is more aligned with your true aspirations. By shedding the unnecessary and the unproductive, you make space for genuine fulfillment and purpose. You are not simply reacting to circumstances, but actively shaping your journey towards meaningful endeavors. Your life becomes a masterpiece painted with deliberate strokes, rather than a chaotic collage of unplanned encounters.

WATCH NOW ▶️ WARNING: Your Brain Thinks Progress Is Danger

FAQs

Why do people often quit when they are almost finished?

People may quit near the end due to fatigue, loss of motivation, fear of failure, or underestimating the effort required to complete the task. Psychological factors like burnout and decreased focus also contribute.

Is it common to feel a drop in motivation near the completion of a project?

Yes, it is common. This phenomenon is sometimes called the “end-of-task slump,” where individuals experience reduced energy and enthusiasm as they approach the finish line.

How can one overcome the urge to quit when close to finishing?

Strategies include setting smaller milestones, reminding oneself of the initial goals, seeking support from others, and focusing on the benefits of completion to maintain motivation.

Does quitting near the end have long-term consequences?

Quitting late in a project can lead to feelings of regret, loss of confidence, and missed opportunities. It may also affect future motivation and the ability to complete similar tasks.

Are there psychological reasons behind quitting just before finishing?

Yes, psychological reasons include fear of success or failure, perfectionism, anxiety about the next steps, and a desire to avoid the stress associated with finalizing a task.